The forthcoming General Election (GE) will not be exclusively concerned with Brexit, but Brexit issues can be expected to loom large. These issues are widely viewed as having disrupted party loyalties and moved electoral politics into a wholly new context, and they have had a disorienting effect on many.

In this essay I want to develop the argument that (a) there is a serious mismatch between the Brexit policies being offered by UK political parties and public preferences/attitudes on relevant Brexit matters, (b) that part at least of the mismatch is attributable to the ‘strategic incompleteness’ of the policies on offer, which in turn appears to be linked to a continuing weakness in analysing the sequencing of policy choices, and (c), as a corollary, there are potential votes to be won by filling in some of the strategic gaps.

The policy stances

First, consider the major national parties’ policies as they appear to stand at the time of writing (noting that they have shown a tendency to move around somewhat):

• Conservative Party (CP): Pass the Withdrawal Bill; sign the Withdrawal Agreement; withdraw from the Treaty of Lisbon in January; negotiate & implement a fairly standard FTA with the EU by the end of the transition period (currently set at 31/12/2020).

• Labour Party (LP): Renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement and/or the Political Declaration to point them to a ‘softer’ Brexit that currently lacks any clear specification, but comes with a strong indication that it should include a CU; then put the provisional agreement to a confirmatory referendum (likely requiring a further extension of the A50 period of around 6 months or more); indicate that the LP, or at least most of its MPs, might vote against the new agreement and in favour of Remain.

• Liberal Democrats (LDs): Revoke the Article 50 notification and remain a member of the EU.

• Brexit Party (BXP): Put the Withdrawal Agreement in the trash can; negotiate a further extension of the A50 period to 30 June 2020; negotiate and implement an FTA with the EU by 1 July 2020; if that proves impossible, simply leave the EU without any overarching trade agreement in place (the No Deal outcome).

Even recognising the necessity of presenting policies in simplified forms, the public is ill served by these offerings. They are saturated with fantasies (about what could be realistically achieved and when), fail to specify policy relating to important elements of the form of separation, and are suffused with vagueness. By way of examples:

• The notion that a new FTA could be negotiated and implemented by end 2020 (CP) or, a fortiori, by end June 2020 and in the absence of a Withdrawal Agreement, is not credible (BXP). It is simply wishful thinking.

• No LD policy is specified for the realistically possible circumstances in which the Government succeeds in achieving withdrawal from the EU by end January 2020 (it’s one of the few aspirations in the list which is realistically attainable), yet those circumstances could eventuate within a few weeks of the General Election. That would render ‘Revoke’ meaningless, leaving the LDs with no policy at all.

• The LP’s notion of the ‘soft’ Brexit it wants to negotiate is ill defined, its feasibility is unexamined/unexplored, and its own position in any subsequent referendum is left vague. It is, in effect, a policy not to have a policy other than rejection of the No Deal possibility, an extended exercise in can kicking.

Part of the general problem is that, when discussing Brexit options, there has been a constant tendency to (i) conflate withdrawal issues and future relationship issues (despite equally constant warnings from experts in the wings that the two should be carefully distinguished), and (ii) conflate the transition period defined by the WA with what I have elsewhere called the ‘interim period’ stretching from Brexit day to the implementation of any new future relationship agreement, see https://gypoliticaleconomy.blog/2018/09/15/brexit-sequencing-and-the-interim-period-problem-limbo-in-our-time/ .

For example, there is constant reference to the WA as ‘the Deal’, when much the more important policy issues are connected with the future relationship agreement (or absence thereof).

Public attitudes

This dog’s breakfast menu put before voters hinders the tasks of (a) informing the public about the relevant issues and trade-offs and (b) inferring public preferences from polling results that, all too frequently, pose chalk and cheese alternatives.

In the general confusion, I continue to rate the attitudinal studies of researchers at King’s College London as the benchmark for sound analysis. It is focused unambiguously on future relationship matters which, in shorthand form, are encompassed by the general question: how close a future relationship do you want to see between the UK and the EU?

(A summary is to be found here, and it is well worth a read in the current context:

https://ukandeu.ac.uk/we-asked-the-british-public-what-kind-of-brexit-they-want-and-the-norway-model-is-the-clear-winner/ )

The potential answers to that question are obviously not binary, i.e. very close or remote: the degree of ‘closeness’ in not to be measured by a single, 0-1, bit of information. The safest inference from the referendum result is simply that a majority of those voting, whose number is almost certainly underestimated by the actual Leave vote (because significant numbers of remain votes will, rationally, have reflected an explicit or implicit assessment that change would just not be worth the hassle), were of the view that a relationship less close than that defined by the Treaty of Lisbon would be preferable.

The KCL study delves deeper into this issue, examining public attitudes on the various, detailed trade-offs that are involved. It does so by working within a conceptual framework that has been a standard part of economics teaching and research for many decades. By way of example, when assessing the likely value of a prospective, complex product that might be put on the market (and policy offerings can be viewed as political ‘products’), the approach seeks to define the main, component characteristics of the product (for a car: engine size and type, fuel efficiency, diesel/petrol, seating capacity, …) and to set about discovering evidence on the values placed on the individual characteristics by consumers. The results can then be used to assess whether the new combination of characteristics in contemplation would be a winner in the market.

Thus, instead of asking the public about their views on, say, a CU – a concept about whose entailments people are likely, like Mr Clarke, to have highly limited knowledge – the main characteristics of a CU are first identified (e.g. ‘how important do you rate the ability of the UK to negotiate its own FTAs’) and respondents are asked about attitudes to them, without mentioning the concept of a CU itself. One major advantage of this in current circumstances is that the meaning of terms like Customs Union and Single Market have become heavily polluted with political associations that influence responses. For example, ‘Mr Mogg dislikes CUs, Mr Clarke likes them, and in general my views are much more closely aligned with Mr Clarke’. (Here, Mr Clarke would be afforded ‘epistemic authority’, even though he is close to clueless on the economic issues at stake and took the CU idea on board for reasons of political expediency).

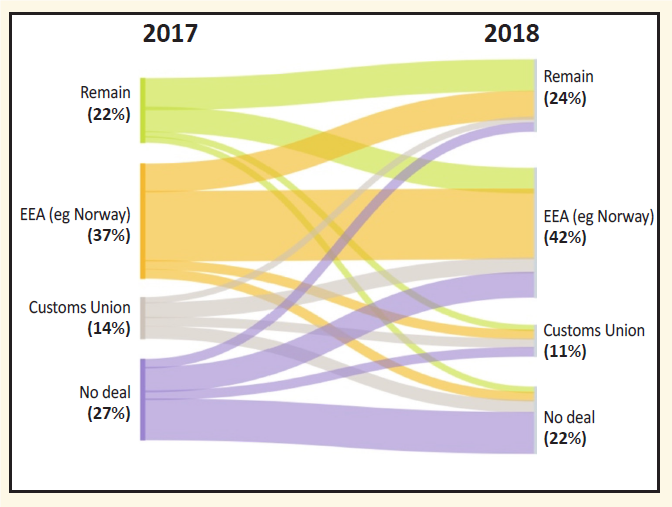

The kinds of characteristics examined in the KCL study encompassed areas like freedom of movement rights, ability to conduct an independent commercial policy, budget contributions, regulatory influence, etc. Intensities of preference of respondents were then aggregated into four bundles that matched four future relationship outcomes: Remain, EEA (Norway), a CU, and No Deal (meaning no future relationship agreement of any significant depth). Each respondent was then allocated to the bundle/label for which that individual’s valuation of the combined characteristics was highest. Results were as follows.

Two points to note immediately are:

• Although there is a substantial body of support for the characteristics of the two end-of-spectrum options (Remain and No Deal), over half the sample had preferences more closely matched with one of the other two options (EEA/Norway and a CU).

• A significant volume of ‘switching’ was recorded in the two years covered by the research, although the totals in the two years are not much different. An immediate inference is that is that there are substantial number of voters who could easily be tipped into another category, i.e. they are not deeply attached to just one option. The thickness of the bands running from Remain to EEA, from EEA to Remain, and from no deal to EEA is striking in this regard. Public attitudes appear much less polarised between outcomes than parliamentary, party activist and media attitudes.

This last point is underpinned by more familiar polling results that indicate that the EEA is viewed by a substantial (not a marginal) majority of respondents as an ‘acceptable’ way forward. Moreover, the results come with an obvious intuition. The underlying trade-offs involved are many and public attitudes to each can be expected to be differentiated. Aggregating over these trade-offs can be expected to lead to a spectrum of valuations of ‘closeness’, not a simple binary division. The latter (the binary division) comes not from public attitudes, but rather from the nature of the referendum question: should the UK remain in or leave the EU?

Given the underlying data on more disaggregated public preferences, it is possible to construct and evaluate public attitudes to other broad policy positions, such as EEA+ (aka Norway+ or CM2.0), which is a combination of EEA/Norway + a Customs Union (CU). The researchers report that they have done this and the results indicated by that exercise are a good demonstration of the value of the approach adopted. Prima facie it might be expected that Norway+ would be closest to the preferences of a larger number of people than unadorned Norway, but the reverse is true. The proportion of the sample for whom the EEA + CU would be the nearest approximation to their preferences falls significantly from the 42% shown for the EEA in 2018.

The reason is that many respondents placed a significant value on the prospect of the UK once again having an independent commercial policy and EEA + CU, unlike EEA alone, would not offer that. These people would, if Norway+ were the only middling option on offer, tend to be switch chiefly to the No Deal category, which in a three-option categorisation, would be the only one offering an independent commercial policy.

That may come as a surprise to some politicians and commentators who read the plus as signifying something that would add value. It is not at all a surprise after a moment’s pause for thought. It implies the delegation, by a major (and ex hypothesi independent) trading nation, of its international trading policy to politicians and bureaucrats of another jurisdiction, and that is not at all a normal occurrence.

The bottom line is that a CU option is a vote loser, which is likely one of the reasons why some of those who have thought about the matter in Paris and Berlin tend to the view that it is unsustainable as a longer term future relationship between the EU and a non-EU UK (another is experience with the Turkish arrangements). Would France and Germany delegate their international commercial policies to a foreign power, with only marginal influence on the conduct of such policies? No, they would not.

Matching policy stances and public attitudes

If the attitudinal results are mapped into the binary question of Remain/Leave, with the additional assumption that the CU category would tilt to the Remain side of the binary, the implication is that, other things equal, the public splits around 65/35 in thinking that the EU is ‘too close’ a relationship for the UK, i.e. that the UK is better out. That, I think is in line with the wider evidence. The UK is, after all, opted out from the EU’s major project, monetary and fiscal union (and the separating effects of that are increasing over time), there is little joy at the prospect of an EU army, and a positive case for EU membership has been noticeably lacking over the past three plus years of Brexit discourse (it has all been very defensive – ‘hold on to nurse for fear of something worse’).

The elevation of the CU issue has been a product of an inward-looking, factional domestic politics, accompanied by large dollops of wilful ignorance and bad faith, but that is only one example of how domestic parties have found themselves wandering in blind alleys and dead ends, remote from where the public would like to see the country. The prospect of a GE, however, allows scope for breaking out of the deadlock.

Given the size of the ‘unserved’ or ‘unrepresented’ (by any major political party) middling view – roughly that the EU is too close a relationship, but considerations of history and geography indicate that the UK should still seek a relationship that is significantly closer than that which it has with most nations on the planet — it would be normal in a democratic system for parties that are more polarised to reach out into that middle in the search for votes. In the business analogue noted above, a company that spotted a large, unserved demand for a product with a combination of characteristics that it could feasibly offer, would likely be leaping at the opportunity to acquire new customers.

What we observe instead is the BXP and LDs going full throttle for the extremes of the ‘closeness/distance spectrum’, the CP being pulled toward the No Deal end of the spectrum in its competition for votes with the BXP, and the LP wandering in space, but drifting slowly toward the Remain end. Given this, the nervousness that is palpable on all sides is understandable. Each strategy is vulnerable to a pivot toward the middle by a competitor (in the business analogue, a rival firm could get to the new product first).

That pivot is most easily achievable by the LDs, because the current LD strategy suffers from an obvious and very major ‘incompleteness’: it contains no statement as to how it would position itself in the (realistically possible, perhaps even likely) event that, in less than three months’ time, the UK will have left the EU. All it has to say is this: ‘Whilst Revoke is our first priority, if that should fail our policy will be to #rEEAmain, i.e. we will fight to keep the UK in the EEA. That exploits the fact that the Treaty of Porto (the EEA Agreement) is a separate treaty from Lisbon and, whilst the WA would see the UK out of the latter, it does not provide for exit from the former. It is the dog that has never barked.

It would also be not that difficult an adjustment for the LP, which has expressed the view that it would like its ill-defined ‘soft Brexit’ outcome to be as close as possible to Single Market arrangements. That could also be crystallized in #rEEAmain, although internal opposition from its now dominant Remain tendency might make that pivot less easy than it potentially is for the LDs, and it appears to be impaired by misreadings of EEAA provisions on state aid, competition policy and freedom of movement on the part of its Marxist ideologues.

These two possibilities make things tricky for the CP. It cannot easily reach out to the unserved middle without risking substantial leakage of votes to the BXP and a revival of its ERG faction. The vanilla FTA in the Political Declaration is there to prevent those things happening: it points to ‘No Deal’ as those words are to be understood in the context of the future relationship, i.e. that there will be no ‘special closeness’ to the EU.

The CP’s one great strategic advantage, on which it almost inevitably has to focus, is that it is the only party in a position to respond to a more immediate, widely shared public desire to get Brexit (in the sense of withdrawal from the Treaty of Lisbon) ‘done and dusted’ as soon as possible. That advantage has just been reinforced by the BXP’s repositioning to a policy that calls for Brexit to be delayed, yet again, until 1 July 2020 (which looks like a mis-step, but opinion polls will soon confirm whether or not that is the case).

The CP’s weaknesses are that (a) the vanilla FTA prospect is publicly unpopular and (b) getting it done by end 2020 is a unicorn: it can be expected to take substantially longer than that. If it could achieve the victory it seeks on 12 December, it could, like the LDs easily pivot toward the centre of gravity of public attitudes (and, in their heart of hearts, ERG members know this, but will likely maintain their tradition of sub-ordinating realities to wishful thinking in the interim). But it is a big ‘if’, possibly conditional on whether the LDs and/or the LP seize the opportunities opened up to them by the existence of a hitherto unserved middle.

Those parties have not done so thus far, but there is nothing like a GE (when politicians do tend to need to give more consideration to voters’ opinions than is the norm) for concentrating minds. With contingency planning in mind, Number 10 might advisedly have a chat with one of the Government’s own Ministers, George Eustice, who has already thought these things through. (Hint: the EEA is a far better place to be, on almost all counts, than in a protracted transition (Limbo), and that is something that can be said early on, without abandoning the first priority of an eventual, new FTA.)